Over on Michael Miles’ blog (Nutrition and Physical Regeneration, which unfortunately appears to be defunct now), Mr. Miles very nicely chronicled how a 23-year-old English major (Denise Minger, the “girl with a blog”) did a thorough academic disembowelment of the ‘research’ of the esteemed T. Colin Campbell, author of the cherry-picking China Study.

I agree that using univariate correlations of population databases should not be used to infer causality, when one adheres to the reductionist philosophy of nutritional biology and/or when one ignores or does not have prior evidence of biological plausibility beforehand. In this case, these correlations can only be used to generate hypotheses for further investigation, that is, to establish biological plausibility. If in contrast, we start with explanatory models that represent the inherent complexity of nutrition and is accompanied by biological plausibility, then it is fair to look for supportive evidence among a collection of correlations…

Read that last sentence carefully. Here’s a translation, in case you had some trouble parsing it: “I believe it’s OK to start with my own beliefs and cherry-pick the data to support them.”

That is precisely the biggest problem in current nutritional “research.”

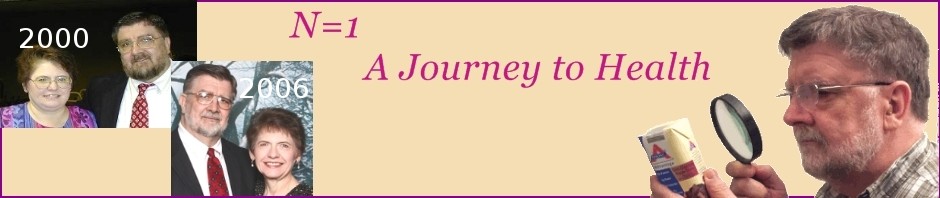

I started noticing problems with nutritional “research” back in 1999, when I started a low-carb diet, and experienced several remarkable health improvements that the mainstream medical community solemnly assured me could not happen. I started following the published papers in the field, and discovered some very important things. First, the field of nutrition more closely resembles religion than it does science. Second, most of the published papers I read would not earn a passing grade in any rigorous college-level biology course. My conclusion was that the current studies, and the mainstream medical community’s interpretation of those studies, were mostly wrong, and in order to find the truth, I would have to try things out for myself. The feedback I got from the newsgroups that I frequented on the the subject of nutrition was mostly in the form of ridicule of my “N=1 Studies,” but I have concluded since that time that my “N=1 Studies” have a much higher validity than most of what passes for “science” in the field of nutrition, for one major reason: My agenda is to figure out how to achieve better health, and most of the industry-funded research has the agenda of convincing the industry to continue to provide funding.